When the Holy Childhood Of Jesus School in Harbor Springs was demolished last fall, so too, perhaps, was some of the evidence of alleged sexual and physical abuse.

That’s the belief of Veronica Pasfield, a University of Michigan doctoral candidate and Bay Mills tribal member. Pasfield is documenting the school’s history, along with the Mount Pleasant Indian Boarding School.

Pasfield learned of the abuse at the school in interviews that she conducted with 36 elders and family members over the last 10 years, including more than 20 interviews for an oral history project for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

Pasfield said she finds it suspicious that the Roman Catholic church is demolishing boarding schools across the country and in Canada and wonders whether it’s to avert the kind of lawsuits that have swamped four Canadian churches to the point of bankruptcy.

“When these boarding schools are taken down, at the very least, what is lost is the daily visual reminder of their legacy,” she said. “By today’s standards, many of these schools are crime scenes. They are also sacred sites in a sense, in the way that a war camp or a battlefield is a sacred site. But until recently the dominant culture recognized the schools as none of that.”

Candace Neff, a spokesperson for Bishop Patrick Cooney and the Gaylord diocese, disputes that view: “Such a suggestion is completely without merit and outrageous,” she said in an email. “It is simply untrue.”

“As we explained before, great time, effort and investigation were undertaken by the parish in order to try to save and renovate the former school building to meet current and future needs. It was only after much study, including that by professionals in architecture, structural engineering, building trades, and getting estimates of what it would cost to renovate, that the parish decided it was not feasible to utilize the existing school building.”

(See sidebar for a continuation of Neff’s comments.)

READ MORE: http://www.northernexpress.com/michigan/article-3760-unholy-childhood.html

WOUNDED SOULS

Elsie Boudreau can relate to the confusion suffered by “Jerry” who felt he loved and was loved by a Roman Catholic nun.

Jerry—not his real name—was one of nine Indian boys who said they were sexually molested by two nuns in the 1960s and 1970s while boarding at the Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. (To read the article in its entirety, go to northernexpress.com).

Jerry believed the relationship was based in “love,” and he’s still coming to terms with its effects. Yet he’s been in and out of rehab nine times and remains a hardcore alcoholic. His two marriages were marred by a lack of fidelity—he has three out-of-wedlock children—and numerous stints in jail. He once aspired to become a state trooper and won entry into University of Michigan, but dropped out after a semester. Now 55, he feels confused and bitter by what happened.

His feelings are par for the course, said Boudreau, a Yup’ik Eskimo from the village of St. Mary’s in Alaska. She was sexually abused during most of her teen years by a Jesuit priest, the Rev. James Poole, who regarded himself as something of a lady’s man.

Her case was settled for $1 million in April.

“I want to put a message out to any victims that if they did feel love, if they felt connected and special to that person, that’s okay. It means they have the capacity to love and that’s good,” she said.

“But my abuser twisted and turned it around and took advantage of that feeling, and that is not okay,” she said.

Jerry—not his real name—was one of nine Indian boys who said they were sexually molested by two nuns in the 1960s and 1970s while boarding at the Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs. (To read the article in its entirety, go to northernexpress.com).

Jerry believed the relationship was based in “love,” and he’s still coming to terms with its effects. Yet he’s been in and out of rehab nine times and remains a hardcore alcoholic. His two marriages were marred by a lack of fidelity—he has three out-of-wedlock children—and numerous stints in jail. He once aspired to become a state trooper and won entry into University of Michigan, but dropped out after a semester. Now 55, he feels confused and bitter by what happened.

His feelings are par for the course, said Boudreau, a Yup’ik Eskimo from the village of St. Mary’s in Alaska. She was sexually abused during most of her teen years by a Jesuit priest, the Rev. James Poole, who regarded himself as something of a lady’s man.

Her case was settled for $1 million in April.

“I want to put a message out to any victims that if they did feel love, if they felt connected and special to that person, that’s okay. It means they have the capacity to love and that’s good,” she said.

“But my abuser twisted and turned it around and took advantage of that feeling, and that is not okay,” she said.

And This:

THE LEGACY OF HOLY CHILDHOOD

This is the third in a four-part series on Holy Childhood School of Jesus. The first two stories on the school in Harbor Springs focused on the sexual abuse of nine young male students at the hands of two Roman Catholic nuns.

On a bleak November day in 1885, a handful of nuns walked into Holy Childhood School of Jesus and began their mission of saving the poor Indian children of Northern Michigan.

So says a 1960 history of the Indian boarding school, which is titled in childlike handwriting on a blackboard: “the problem can be solved.”

The school was run by the School Sisters of Notre Dame, an international group of Catholic nuns that remains devoted to schooling underprivileged children. It ran on a shoestring budget and relied on local people and church members for money.

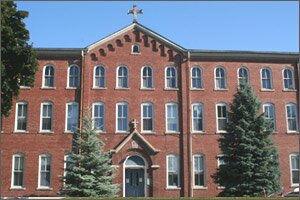

The school opened in 1829 as a small log cabin. It grew into a stately three-story building and closed in 1983 due to low enrollment. The building was demolished last fall, with a new parish building to rise in its stead.

With such a long history, there is no single way to characterize the boarding school. But if you are a middle-aged Native American and a former student, chances are good that you’ll never forget the Roman Catholic nuns of Holy Childhood School.

On a bleak November day in 1885, a handful of nuns walked into Holy Childhood School of Jesus and began their mission of saving the poor Indian children of Northern Michigan.

So says a 1960 history of the Indian boarding school, which is titled in childlike handwriting on a blackboard: “the problem can be solved.”

The school was run by the School Sisters of Notre Dame, an international group of Catholic nuns that remains devoted to schooling underprivileged children. It ran on a shoestring budget and relied on local people and church members for money.

The school opened in 1829 as a small log cabin. It grew into a stately three-story building and closed in 1983 due to low enrollment. The building was demolished last fall, with a new parish building to rise in its stead.

With such a long history, there is no single way to characterize the boarding school. But if you are a middle-aged Native American and a former student, chances are good that you’ll never forget the Roman Catholic nuns of Holy Childhood School.

THEY CAME FOR THE CHILDREN

The Holy Childhood School of Jesus was demolished last fall, but former students say they’ll never forget their formative years at the Indian boarding school. This is the final story of a series that has focused on the school’s legacy.

The Holy Childhood School of Jesus was established by Catholic nuns with the mission of helping impoverished Indian children and raising them in the Roman Catholic faith. But it was just one of scores of boarding schools established by religious groups or the U.S. government that took in tens of thousands of Indian children in a misguided social experiment.

The Harbor Springs school, founded in 1829, was one of the earliest Indian boarding schools in the country. Like thousands of Indian children across the country, the students began boarding school life at the age of six or seven and returned home at the age of 14. Holy Childhood closed in 1983 due to low enrollment, money problems, and staff shortages.

The question is, why boarding schools?

The church’s mission was obvious—to help children, some of them from deeply troubled homes, and to raise them as Christians, be it Episcopalian, Methodist or Catholic. The government’s motives had more to do with “civilizing” the savage man. The third reason is economic. University of Michigan doctoral student Veronica Pasfield contends that off-reservation boarding schools and federal policies worked synergistically to seize or control a tribe’s property and other assets. Such rich resources were desperately needed by a post-Civil War economy at a time when the country was swiftly industrializing, she said.

The Holy Childhood School in Harbor Springs was founded in the early 19th century in a tiny log cabin, decades earlier than the first off-reservation government school of 1879.

The Holy Childhood School of Jesus was established by Catholic nuns with the mission of helping impoverished Indian children and raising them in the Roman Catholic faith. But it was just one of scores of boarding schools established by religious groups or the U.S. government that took in tens of thousands of Indian children in a misguided social experiment.

The Harbor Springs school, founded in 1829, was one of the earliest Indian boarding schools in the country. Like thousands of Indian children across the country, the students began boarding school life at the age of six or seven and returned home at the age of 14. Holy Childhood closed in 1983 due to low enrollment, money problems, and staff shortages.

The question is, why boarding schools?

The church’s mission was obvious—to help children, some of them from deeply troubled homes, and to raise them as Christians, be it Episcopalian, Methodist or Catholic. The government’s motives had more to do with “civilizing” the savage man. The third reason is economic. University of Michigan doctoral student Veronica Pasfield contends that off-reservation boarding schools and federal policies worked synergistically to seize or control a tribe’s property and other assets. Such rich resources were desperately needed by a post-Civil War economy at a time when the country was swiftly industrializing, she said.

The Holy Childhood School in Harbor Springs was founded in the early 19th century in a tiny log cabin, decades earlier than the first off-reservation government school of 1879.

READ MORE: http://www.northernexpress.com/michigan/article-3658-they-came-for-the-children.html

No comments:

Post a Comment