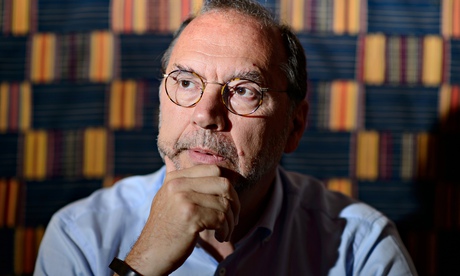

Professor Peter Piot, the Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: ‘Around June it became clear to me there was something different about this outbreak. I began to get really worried’ Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP

Professor Piot, as a young scientist in Antwerp, you were part of the team that discovered the Ebolavirus in 1976. How did it happen?

I still remember exactly. One day in September, a pilot from Sabena Airlines brought us a shiny blue Thermos and a letter from a doctor in Kinshasa in what was then Zaire. In the Thermos, he wrote, there was a blood sample from a Belgian nun who had recently fallen ill from a mysterious sickness in Yambuku, a remote village in the northern part of the country. He asked us to test the sample for yellow fever.

These days, Ebola may only be researched in high-security laboratories. How did you protect yourself back then?

We had no idea how dangerous the virus was. And there were no high-security labs in Belgium. We just wore our white lab coats and protective gloves. When we opened the Thermos, the ice inside had largely melted and one of the vials had broken. Blood and glass shards were floating in the ice water. We fished the other, intact, test tube out of the slop and began examining the blood for pathogens, using the methods that were standard at the time.

But the yellow fever virus apparently had nothing to do with the nun’s illness.

No. And the tests for Lassa fever and typhoid were also negative. What, then, could it be? Our hopes were dependent on being able to isolate the virus from the sample. To do so, we injected it into mice and other lab animals. At first nothing happened for several days. We thought that perhaps the pathogen had been damaged from insufficient refrigeration in the Thermos. But then one animal after the next began to die. We began to realise that the sample contained something quite deadly.

But you continued?

Other samples from the nun, who had since died, arrived from Kinshasa. When we were just about able to begin examining the virus under an electron microscope, the World Health Organisation instructed us to send all of our samples to a high-security lab in England. But my boss at the time wanted to bring our work to conclusion no matter what. He grabbed a vial containing virus material to examine it, but his hand was shaking and he dropped it on a colleague’s foot. The vial shattered. My only thought was: “Oh, shit!” We immediately disinfected everything, and luckily our colleague was wearing thick leather shoes. Nothing happened to any of us.

In the end, you were finally able to create an image of the virus using the electron microscope.

Yes, and our first thought was: “What the hell is that?” The virus that we had spent so much time searching for was very big, very long and worm-like. It had no similarities with yellow fever. Rather, it looked like the extremely dangerous Marburg virus which, like ebola, causes a haemorrhagic fever. In the 1960s the virus killed several laboratory workers in Marburg, Germany.

No comments:

Post a Comment